Velupillai Prabakaran History In Tamil Pdf

If there was ever a competition to find the person who summed up the adage which says that 'one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter', then Velupillai Prabhakaran, the rotund but fearsome leader of the Tamil Tigers, would have been a strong candidate. For nearly 30 years, the moustachioed commander's brutal war to create an independent 'Eelam' (homeland) for Sri Lanka's minority Tamils teetered on the often thin line between a struggle for liberation and outright terrorism.

Velupillai Prabhakaran was born in the northern coastal town of Valvettithurai on November 26, 1954, as the youngest of four children to Thiruvenkadam Velupillai and his wife Vallipuram Parvathy. Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), commonly known as the Tamil Tigers, is a militant organization that has been waging a violent secessionist campaign against the Sri Lankan government since the 1970s in order to create a separate Tamil state in the north and east of Sri Lanka. வேலுப்பிள்ளை பிரபாகரனின் வாழ்க்கை வரலாறு velupillai prabhakaran history in tamil TAMIL.

To his detractors, the founder of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) was little more than a ruthless terrorist who pioneered the use of suicide bombings to assassinate two heads of state, viciously annihilated his own Tamil critics and stubbornly refused any compromise that might have led to peace. Yet to the thousands of fighters who followed him to their deaths, and to the millions of Tamils scattered around the world who donated handsomely to the LTTE's coffers, the reticent 54-year-old was a hero and demigod.

Lovingly referred to by his Tamil nickname, 'Thamby' (little brother), Prabhakaran was viewed by his people as the only man capable of defending Tamil Eelam against Sri Lanka's modern, foreign-funded army and the numerous human-rights violations perpetrated by the country's Buddhist, Sinhalese-dominated central government. His skills as a brilliant military strategist were beyond doubt. By creating an immensely powerful personality cult and a suicide ethos among his fanatically loyal fighters, the LTTE was able to keep a conventional army at bay for decades using little more than assault rifles. But Prabhakaran's willingness to resort to assassinations, random attacks on civilians, the recruitment of child soldiers and the eradication of any democratic Tamil opposition left his Tigers with a bitterly controversial legacy that will haunt Tamil nationalism for many years to come.

We’ll tell you what’s true. You can form your own view.

From 15p€0.18$0.18USD 0.27 a day, more exclusives, analysis and extras.

For the briefest of moments it could have been so very different. The last time that The Independent met the elusive leader was seven years ago, in an iron shed in the now ravaged town of Kilinochchi. Prabhakaran rarely gave interviews and the few journalists who did manage to meet him usually had to go through days of Tiger checkpoints, searches and intense security measures – not to mention the fear of falling victim to a Sri Lankan air strike or artillery shell. But in April 2002 a potential peace was in the air. Sri Lankans had just voted in their new president, Ranil Wickremasinghe, a relative dove who had campaigned on a platform offering talks to the LTTE. Feeling the pressure to distance himself and the Tigers from terrorism post-11 September, Prabhakaran agreed and briefly came out of the jungle to announce that the Tigers were now 'committed to peace'.

When he addressed the gathered journalists, the signature tiger-stripe camouflage uniform and sidearm that he had always worn had been replaced with a more palatable high-buttoned bush jacket. The cyanide capsule worn around his neck as a last resort also remained hidden. But the high-pitched voice was the same, a soft demeanour which belied Prabhakaran's unwillingness to give up the gun. In fact, most people who met him were surprised that such a quietly spoken man could be the feared and brutal leader he was known to be. Eventually the peace talks stalled, Wickremasinghe lost the next presidential election to the hardliner Mahinda Rajapaksa and Prabhakaran's fate was slowly sealed.

He was the middle-class son of a pious government-employed agronomist; Prabhakaran's descent into violence was swift and brutal. Born on 26 November 1954 in the northern coastal town of Valvettithurai, Prabhakaran almost single-handedly ignited the Tamil insurgency when he was 21 by assassinating the governor of Jaffna. His ragtag gang of young nationalists calmly walked up to the governor outside a Hindu temple and gunned him down.

Velupillai Prabhakaran History In Tamil

Decades of Sinhalese domination and anti-Tamil policies had created a wealth of seething anger among Sri Lanka's Tamils; Prabhakaran's bullet was the spark that finally set the island alight. Fleeing into the jungle, he set up the LTTE, which quickly became the most effective, efficient and ruthless Tamil rebel group fighting the government.

Long before Islamic jihadists realised the effectiveness of suicide bombs, LTTE cadres from the group's fanatical Black Tiger regiment, many of whom were women, carried out a series of spectacular assassinations, including the murder of India's prime minister Rajiv Gandhi in 1991 and the Sri Lankan president Ranasinghe Premadasa two years later. The attacks were a terrifying but strategically brilliant weapon which could rarely be stopped and struck fear into the hearts of ordinary Sri Lankans.

To explain the Tiger's internecine massacres, the English-speaking Tamil Tiger ideologue Anton Balasingham once remarked: 'Down the history of liberation struggles all over the world, the big fish swallows the smaller fish. In the end, only the big fish remains.' Prabhakaran was determined to make sure that he was the only big fish around.

Initially enforcing a vow of chastity on his fanatical fighters, Prabhakaran went on to marry Mathivathani Erambu, a fiery and beautiful student who had vowed to fast to death in support of Tamil Eelam in 1983. Prabhakaran was living in south India at the time and was so determined to control every aspect of the Tamil rebellion that he had the students kidnapped and taken to his compound in Chennai. During the Hindu festival of Holi, Mathivathani had the audacity to throw a bucket of coloured water at the Tamil Tiger leader, who, impressed by her bravery, fell deeply in love. The chastity vow broken, the couple married and went on to have three children, a daughter named Duwaraka, and two sons, Balachandran and Charles Anthony. The latter is thought to be his father's successor. Tamil Tiger cadres are now allowed to marry, but only after five years of military service.

In many ways, the assassination of Gandhi, in retaliation for the stationing of Indian troops in Sri Lanka, was Prabhakaran's biggest single tactical error. It turned India's generally moderate Tamil population against him, alienated sympathetic allies in Gandhi's Congress Party and reinforced the belief abroad that the LTTE was a violent, terrorist entity that the international community simply could not do business with.

More recently, his second largest mistake was to forbid Tamils from voting in the 2005 presidential election, a decision which allowed his arch-enemy Rajapaksa to take the reigns of power and begin the assault that eventually led to Prabhakaran's death and the military destruction of his organisation. The ruthlessness with which the Tigers eradicated any Tamil opposition also left the Eelam movement lacking any sort of political wing that might have constituted a more palatable public face. And Prabhakaran also made enemies within his own movement.

In March 2004, Colonel Karuna, an LTTE commander of 20 years and a close friend of Prabhakaran, publicly broke away from the Tigers and eventually handed over a vast swathe of eastern Sri Lanka to Colombo. Karuna, a feared warlord turned 'integration minister', whom human rights groups have accused of multiple abuses since defecting, brought crucial intelligence with him on the LTTE that helped Rajapaksa prepare for his final assault.

M.R. Narayan Swamy, an Indian journalist who has written the only in-depth biography of Prabhakaran, maintains that opinions of the Tamil Tiger leader among Tamils will always remain mixed. 'There will be no single legacy for Prabhakaran among Tamils,' he said. 'For many he will always be that god-like figure who was a great fighter and a hero. But after 26 years of brutal war there will be some who will start asking whether it was really worth it.' Microsoft windows server 2012 r2 das handbuch.

But without their leader, Swamy believes, the Tigers will never be the same again. 'The LTTE only ever had one leader and only one god. When that god dies, the Tigers will cease to exist. After nearly 30 years of war there is no appetite to begin another armed struggle and the LTTE will never be the same again.'

Jerome Taylor

Velupillai Prabhakaran, founder and leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam: born Valvettithurai, Sri Lanka 26 November 1954; married 1984 Mathivathani Erambu (two sons, one daughter); died Sri Lanka 18 May 2009.

Jump to navigationJump to searchPrabhakaran in November 2006 | |

| Native name | |

|---|---|

| Born | 26 November 1954 Valvettithurai, Dominion of Ceylon[1][1][2][3] |

| Died | 19 May 2009 (aged 54) |

| Cause of death | Killed in a decisive operation by SASF on 18 May 2009[4] |

| Nationality | Sri Lankan |

| Other names | Karikalan |

| Occupation | Founder & Leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) movement in Sri Lanka. |

| Known for | Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism |

| Criminal charge | Planning assassination of Rajiv Gandhi in 1991[5][6] Colombo Central Bank bombing of 1996[6] |

| Criminal penalty | Arrest warrant issued by Colombo High Court[7] Death warrant issued by Madras High Court, India.[8] Sentenced to 200 years in prison by Colombo High Court.[6][9] |

| Spouse(s) | Mathivathani Erambu (1984–2009) † |

| Children | Charles Anthony (1989–2009) †[10] Duvaraga (1986–2009) †[11] Balachandran (1997–2009) †[12] |

| Part of a series on |

| Sri Lankan Tamils |

|---|

Thiruvenkadam Velupillai Prabhakaran (listen (US English); Tamil: வேலுப்பிள்ளை பிரபாகரன்; Tamil pronunciation: [ˈʋeːlɯpːɨɭːɛi̯ prəˈbɑːɦərən], 26 November 1954 – 19 May 2009) was the founder and leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (the LTTE or the Tamil Tigers), a militant organization that sought to create an independent Tamil state in the north and east of Sri Lanka.[13]

For over 25 years, the LTTE waged war in Sri Lanka to create an independent state for the Sri Lankan Tamil people. Founded in 1976, the LTTE rocketed to prominence in 1983 after they ambushed a patrol of the Sri Lanka Army outside Jaffna, resulting in the deaths of 13 soldiers. This ambush, along with the subsequent rioting which resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Tamil civilians, is generally considered the start of the Sri Lankan Civil War. After years of fighting, including the intervention of the Indian Army (IPKF), the conflict was halted after international mediation in 2001. By then, the LTTE also known as the Tamil Tigers controlled large swathes of land in the north and east of the country, running a de facto state with Prabhakaran serving as its leader.[14] Peace talks eventually broke down, and the Sri Lanka Army launched a military campaign to defeat the Tamil Tigers in 2006.

Prabhakaran and his son Charles Anthony were killed in fighting with the Sri Lankan Army in May 2009.[15] His wife's and daughter's bodies were reportedly found by the Sri Lankan army but the report was later denied by the Sri Lankan government.[16] It was alleged that his 12-year-old second son was executed a short time later.[17] Prabhakaran's reported death and the announcement 'We have decided to silence our guns. Our only regrets are for the lives lost and that we could not hold out for longer,' by Selvarasa Pathmanathan, the Tigers' chief of international relations, brought an end to the armed conflict.[18]

- 2Tamil Tigers

- 3Philosophy and ideology

- 10External links

Early life[edit]

Velupillai Prabhakaran was born in the northern coastal town of Valvettithurai on 26 November 1954, as the youngest of four children [19][20] to Thiruvenkadam Velupillai and his wife Vallipuram Parvathy.[21][22] Thiruvenkadam Velupillai was the District land Officer in the Ceylon Government[20][23] His family was an influential and wealthy family who owned and managed the major Hindu temples in Valvettithurai.[24][25]

Angered by what he saw as discrimination against Tamil people by successive Sri Lankan governments, he joined the student group Tamil Youth Front (TYF) during the standardisation debates.[26] In 1972 Prabhakaran founded the Tamil New Tigers (TNT)[20][27] which was a successor to many earlier organizations that protested against the post-colonial political direction of the country, in which the minority Sri Lankan Tamils were pitted against the majority Sinhalese people.[28][29]

In 1975, after becoming heavily involved in the Tamil movement, he carried out the first major political assassination by a Tamil group, killing the mayor of Jaffna, Alfred Duraiappah, by shooting him at point-blank range when he was about to enter the Hindu temple at Ponnaalai. The assassination was in response to the 1974 Tamil conference incident, for which the Tamil radicals had blamed Duraiappah,[30] because he backed the then ruling Sri Lanka Freedom Party.[31]

Tamil Tigers[edit]

Founding of the LTTE[edit]

In the early 1970s, United Front government of Sirimavo Bandaranaike introduced the Policy of standardisation which made the criteria for university admission lower for the Sinhalese than for the Tamils.[32] Several organizations to counter this act was formed by Tamil students. Prabhakaran aged 15, dropped out of school and got associated with the Kuttimani-Thangathuraigroup (which evolved later into TELO) formed by Selvarajah Yogachandran (known as Kuttimani) and Nadarajah Thangathurai who both also hailed from Valvettithurai.[33]

Prabhakaran along with Kuttimani, Ponnuthurai Sivakumaran and other prominent rebels joined the Tamil Manavar Peravai formed by a student named Satiyaseelan in 1970. This group comprised Tamil youth who advocated the rights of students to have fair enrollment.[34][note 1]

In 1973, Prabhakaran teamed up with Chetti Thanabalasingam and with a fraction of the Tamil Manavar Peravai to form the Tamil New Tigers (TNT).[36][37] Their first notable attack was held at the Duraiappa stadium in Jaffna placing a bomb in an attempt to murder the Jaffna Mayor Alfred Duraiappah.[38] A member of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party who was loyal to Sirimavo Bandaranaike, Duraiappah was seen as a traitor by the Tamil masses.[39] Failing the attempt, Prabhakaran managed to shoot and kill Duraiappah who was on a visit at a Hindu temple at Ponnalai on the 27th July 1975.[40]

On 5 May 1976, the TNT was renamed the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), commonly known as the Tamil Tigers.[41] The LTTE by the 1980s operated in more attacks against police and military forces. On the 23rd July 1983, the LTTE ambushed an army patrol and killed 13 Sri Lankan soldiers in Thirunelveli, Sri Lanka.[39] As a response to this were one of the worst government sponsored anti-Tamil riots held (the event known as Black July) resulting in the destruction of Tamil houses and shops and death of hundreds of Tamils and making over 150 000 Tamils homeless.[42][43]As a result of the riots were several Tamils joining the LTTE and the LTTE marked the beginning of the Eelam War I.[44] Prabhakaran held his first speech on the 4th August 1987 at the Suthumalai Amman temple in front of over 100 000 people explaining the position of the LTTE.[45] This speech is seen as a historic turning point in the Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism.[46]

The LTTE were allegedly involved in the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, the ex-prime minister of India in 1991, which they denied involvement and alleged the event as an international conspiracy against them[47][48] The Madras High Court in India issued an arrest warrant for plotting of the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi and Prabhakaran was made wanted by Interpol for terrorism, murder, organized crime and terrorism conspiracy.[49] Prabhakaran's first and only major press conference was held in Killinochchi on 10 April 2002.[50] It was reported that more than 200 journalists from the local and foreign media attended this event and they had to go through a 10-hour security screening before the event in which Anton Balasingham introduced the LTTE leader as the 'President and Prime minister of Tamil Eelam.'

A number of questions were asked about LTTE's commitment towards the erstwhile peace process and Prabhakaran and Dr. Anton Balasingham jointly answered the questions.

Repeated questions of his involvement in the Rajiv Gandhi assassination were only answered in a sober note by both Balasingham and Prabhakaran. They called it a 'tragic incident' ('Thunbiyal Chambavam', as quoted in Tamil) they requested the press 'not to dig into an incident that happened 10 years ago.'[This quote needs a citation]

During the interview he stated that the right condition has not risen to give up the demand of Tamil Eelam. He further mentioned that 'There are three fundamentals. That is Tamil homeland, Tamil nationality and Tamil right to self-determination. These are the fundamental demands of the Tamil people. Once these demands are accepted or a political solution is put forward by recognising these three fundamentals and our people are satisfied with the solutions we will consider giving up the demand for Eelam.' He further added that Tamil Eelam was not only the demand of the LTTE but also the demand of the Tamil people.[50]

Prabhakaran also answered a number of questions in which he reaffirmed their commitment towards peace process, quoted 'We are sincerely committed to the peace process. It is because we are sincerely committed to peace that we continued a four month cessation of hostilities' was also firm in de-proscription of the LTTE by Sri Lanka and India, 'We want the government of India to lift the ban on the LTTE. We will raise the issue at the appropriate time.'

Prabhakaran also insisted firmly that only de-proscription would bring forth an amenable solution to the ongoing peace process mediated by Norway: 'We have informed the government, we have told the Norwegians that de-proscription is a necessary condition for the commencements of talks.'[51][52]

Philosophy and ideology[edit]

Prabhakaran was fascinated by Napoleon and Alexander the Great. He was also highly influenced by prominent Indian nationalists Subhas Chandra Bose and Bhagat Singh who fought the British Empire.[53] Prabhakaran never developed a systematic philosophy, but did declare that his goal was 'Revolutionary socialism and the creation of an egalitarian society'. His rare interviews, his annual Tamil Eelam Heroes Day speeches and the policies and actions of the LTTE can be taken as indicators of Prabhakaran's philosophy and ideology. Religion was not a major factor in his philosophy or ideology, the ideology of the Tamil Tigers emerged from Marxist-Leninist thought, and was explicitly secular. Its leadership professed opposition to religion.[54][55][56] Their focus was on a single-minded approach toward the attainment of an independent Tamil Eelam. The following are important areas when considering the philosophy and ideology of Prabhakaran.

Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism[edit]

Prabhakaran's source of inspiration and direction was Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism. His stated and ultimate ideal was to get Tamil Eelam recognised as a nation as per the U.N. Charter that guarantees the right of a people to political independence.[57] The LTTE also proposed the formation of an Interim Self Governing Authority during Peace Negotiations in 2003. Former Tamil guerrilla and politician Dharmalingam Sithadthan has remarked that Prabhakaran's 'dedication to the cause of the Tamil Eelam was unquestionable, he was the only man in Sri Lanka who could decide if there should be war or peace.'[58] Prabhakaran was also called 'Karikalan' for his bravery and his administration (in reference to Karikala Chola, a famous Chola king who ruled in Sangam Age.)

Militarism of the LTTE[edit]

Prabhakaran explicitly stated that an armed struggle is the only way to resist asymmetric warfare, in which one side, that of the Sri Lankan government, is armed and the other comparatively unarmed. He argued that he chose military means only after observing that non–violent means have been ineffectual and obsolete, especially after the Thileepan incident. Thileepan, a colonel rank officer adopted Gandhian means to protest against the IPKF killings by staging a fast unto death from 15 September 1987, and by abstaining from food or water until 26 September, when he died in front of thousands of Tamils who had come there to fast along with him.[59]

Tactically, Prabhakaran perfected the recruitment and use of suicide bomber units. Casas modernas para los sims 3 sin expansiones. His fighters usually took no prisoners and were notorious for assaults that often left every single enemy soldier dead.[58]Interpol described him as someone who was 'very alert, known to use disguise and capable of handling sophisticated weaponry and explosives.'[58]

Death[edit]

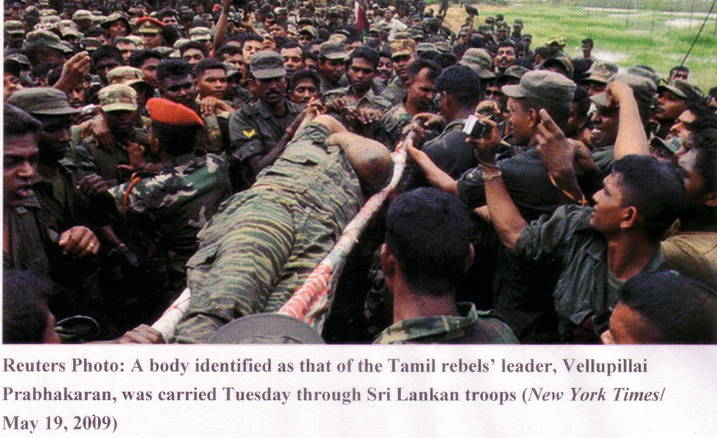

When the Sri Lankan military rapidly advanced into the last LTTE held territory in the final days of 2008–2009 SLA Northern offensive, Prabhakaran and his top leadership retreated into Vellamullivaikkal, Mullaitivu. Fierce fighting occurred between LTTE and the Sri Lanka Army during these last few days. At around 3:00 a.m. on 18 May 2009, Prabhakaran's son Charles Anthony tried to break the defenses of the Army, but was unsuccessful. He died along with around 100 other LTTE fighters. Troops found 12 million rupees in his possession.[15] By the noon of that day, reports emerged that Prabhakaran was killed by a rocket attack while trying to flee the conflict zone in a captured ambulance and his body was badly burned.[60] But this rumour was proven false in a short while. Skirmishes occurred also in the evening of 18 May around eastern bank of Nandikadal lagoon. A team of LTTE cadres consisting of 30 most loyal bodyguards of Prabhakaran and Prabhakaran himself tried to sneak through the mangrove islands of Nandikadal to its west bank. It has been alleged that one bodyguard had a can of gasoline with him to burn the Tiger leader's body if he was killed or committed suicide. This was to prevent the enemy seizing his body.[61] Clearing and mopping-up operations were carried out by troops under Colonel G. V. Ravipriya from 3:30 pm to 6:30 pm that evening, but they did not encounter this last group of LTTE fighters that day. At 7:30 am next morning, mopping-up operations started again. This time, they were confronted by the fighters, led by Prabhakaran himself. Fighting went on until 9:30 am 19 May 2009. The firing stopped as all LTTE fighters died in the battle. Troops started collecting bodies again. This time, Sergeant Muthu Banda, attached to Sri Lanka Army Task Force VIII, reported to Ravipriya that a body similar to Prabhakaran's had been found. After the body, which was floating among the mangroves, was brought ashore, Colonel Ravipriya positively identified it as that of the leader of the LTTE.[15] A dog tag marked 001, two pistols, a T56 rifle with telescopic sight, a satellite phone, and a canister filled with diabetic medicine were found along with the body.

• Title screen is the same regardless of your settings. Patch chrono trigger ds rom.

At 12:15 pm army commander Sarath Fonseka officially announced Prabhakaran's death on TV. At around 1:00 pm his body was shown in Swarnavahini for the first time.[62] Prabakaran's identity was confirmed by Karuna Amman, his former confidant, and through DNA testing against genetic material from his son, who had been killed earlier by the Sri Lankan military.[63] Circumstantial evidence suggested that his death was caused by massive head trauma, several claims on his death have been made and its alleged that his death is due to a shot at close range. There are also allegations that he was executed, a claim vehemently denied by Sri Lankan authorities. Karuna Amman claimed Prabhakaran shot himself but it was denied by Fonseka who claimed the injury was from shrapnel citing the lack of an exit wound.[64] A week later, the new Tamil Tiger leader, Selvarasa Pathmanathan, admitted that Prabhakaran was dead.[65][66]

Personal life[edit]

Prabhakaran was married to Mathivathani Erambu on 1 October 1984.[67][68] The military spokesman Udaya Nanayakkara stated in May 2009, that there was no information about the whereabouts of the remaining members of the Prabhakaran's family. “We have not found their bodies and have no information about them,” he said.[69] However, it is thought that the entire Prabhakaran family has been wiped out; the bodies of Mathivathani, Duvaraga and Balachandran reportedly were found in a bushy patch about 600 meters away from where Prabhakaran's body was found.[70] It is now believed that his 12-year-old son was executed.[71]

Velupillai Prabhakaran's parents, Thiruvenkadam Velupillai and Parvathi, both in their 70s, were found in the Menik Farmcamp for displaced people near the town of Vavuniya. The Sri Lankan military and the government gave public assurances that they would not be interrogated, harmed or ill-treated.[72] Prabhakaran's parents were then taken into Sri Lankan military custody until the death of Mr Vellupillai in January 2010.[73] Prabhakaran has a sister named Vinodini Rajendaran.[74][75]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^The name is variously translated as Tamil Students League or Tamil Students Federation, later also known as Tamil Ilaynar Peravai (TIP) translated as Tamil Youth Front (TYF)[35]

References[edit]

- ^ ab'Lanka army sources'. Times of India. 18 May 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^Bosleigh, Robert (18 May 2009). 'Tamil Tigers supreme commander Prabhakaran 'shot dead''. London: Times Online. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^Nelson, Dean (18 May 2009). 'Tamil Tiger leader Velupillai Prabhakaran 'shot dead''. London: Telegraph. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ^'Tiger leader Prabhakaran killed: Sources-News-Videos-The Times of India'. The Times of India. 18 May 2009. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ^'Rajiv Gandhi assassination: Agency probing killing conspiracy plods on'. Times of India. 20 May 2011.

- ^ abc'Rebel leader sentenced to 200 years' jail as talks start'. The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 November 2002. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^'Colombo High Court Issue arrest warrant for Prabhakaran and Pottu Amman'. Asian Tribune. 13 May 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^'Obituary: Velupillai Prabhakaran'. BBC. 18 May 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^Mydans, Seth (2 November 2002). 'Rebels Protest Leader's Sentence'. New York Times. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^'Prabhakaran's son dead'. Mid-day.com. 18 May 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^'National Leader Prabakaran's Daughter Dwaraka's photos released – Most Shocking'. LankasriNews.com. 16 December 2009. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^'BBC News – Balachandran Prabhakaran: Sri Lanka army accused over death'. BBC. 19 February 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^'Tamil Tigers'. Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^Lahiri, Simanti (3 April 2014). Suicide Protest in South Asia: Consumed by Commitment. Routledge. p. 108. ISBN9781317803133.

- ^ abc'No peace offer from Prabhakaran – only war'. Lanka Web. 11 June 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^Anderson, Jon Lee (10 January 2011). 'Death of the Tiger'. The New Yorker. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^Mcrae, Callum (19 February 2013). 'The Killing of a Young Boy'. The Hindu. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^Nelson, Dean (18 May 2009). 'Tamil Tiger leader Velupillai Prabhakaran 'shot dead''. The Telegraph. ISSN0307-1235. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^'Obituary: Velupillai Prabhakaran'. BBC News. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ abcPrabhakaran, Veluppillai and the father-son relationship – DBS Jeyara Accessed 25 November 2016

- ^'First Political Assassination Of Prabhakaran'. Lankapuwath. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^'Profile of Velupillai Prabhakaran'. Lankapuwath. 22 April 2009. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^Chellamuthu Kuppusamy (1 December 2008). பிரபாகரன்: ஒரு வாழ்க்கை / Prabhakaran: Oru Vaazhkai [Prabhakaran: A Life]. New Horizon Media. p. 28. ISBN978-81-8493-039-9.

- ^Wilson, A. Jeyaratnam (2000). Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. UBC Press. ISBN9780774807593.

- ^Wadley, Susan S. (18 December 2014). South Asia in the World: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 206. ISBN9781317459590.

- ^Tawil, Sobhi; Harley, Alexandra (1 January 2004). Education, Conflict and Social Cohesion. Unesco, International Bureau of Education. p. 388. ISBN9789231039621.

- ^Heilmann-Rajanayagam, Dagmar (1994). The Tamil Tigers: Armed Struggle for Identity. Stuttgart, Germany: Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 37–38.

- ^Sunil Bastian (September 1999) The Failure of State Formation, Identity Conflict and Civil Society Responses – The Case of Sri Lanka. Working Paper 2, Centre for Conflict Resolution, Department of Peace Studies, University of Bradford

- ^How it Came to This – Learning from Sri Lanka’s Civil Wars. paradisepoisoned.com. Retrieved on 2012-06-22.

- ^'Welcome to UTHR, Sri Lanka'. Uthr.org. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ^'Asia Times: Sri Lanka: The Untold Story'. Atimes.com. 26 January 2002. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ^Dharmawardhane, Iromi (2014). Sri Lanka's Post-conflict Strategy: Restorative Justice for Rebels and Rebuilding of Conflict-affected Communities. Research & Monitoring Division, Department of Government Information, Sri Lanka. p. 16. ISBN9789559073284.

- ^Amarasingam, Amarnath (15 September 2015). Pain, Pride, and Politics: Social Movement Activism and the Sri Lankan Tamil Diaspora in Canada. University of Georgia Press. p. 25. ISBN9780820348148.

- ^Gunaratna, Rohan (1993). Indian intervention in Sri Lanka: the role of India's intelligence agencies. South Asian Network on Conflict Research. p. 66. ISBN9789559519904.

- ^Richardson, John Martin (2005). Paradise Poisoned: Learning about Conflict, Terrorism, and Development from Sri Lanka's Civil Wars. International Center for Ethnic Studies. p. 350. ISBN9789555800945.

- ^Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. Published under the auspices of the Pakistan American Foundation. 2007. p. 81.

- ^Rinehart, Christine Sixta (2013). Volatile Social Movements and the Origins of Terrorism: The Radicalization of Change. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 126. ISBN9780739177709.

- ^Talpahewa, Dr Chanaka (28 May 2015). Peaceful Intervention in Intra-State Conflicts: Norwegian Involvement in the Sri Lankan Peace Process. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 34. ISBN9781472445353.

- ^ abDeVotta, Neil (2004). Blowback: Linguistic Nationalism, Institutional Decay, and Ethnic Conflict in Sri Lanka. Stanford University Press. p. 169. ISBN9780804749244.

- ^Amarasingam, Amarnath (15 September 2015). Pain, Pride, and Politics: Social Movement Activism and the Sri Lankan Tamil Diaspora in Canada. University of Georgia Press. p. 26. ISBN9780820348148.

- ^Rinehart, Christine Sixta (2013). Volatile Social Movements and the Origins of Terrorism: The Radicalization of Change. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 118. ISBN9780739177709.

- ^Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. Published under the auspices of the Pakistan American Foundation. 2007. p. 83.

- ^Aspinall, Edward; Jeffrey, Robin; Regan, Anthony (2 October 2012). Diminishing Conflicts in Asia and the Pacific: Why Some Subside and Others Don't. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN9781136251139.

- ^Hashim, Ahmed (2013). When Counterinsurgency Wins: Sri Lanka's Defeat of the Tamil Tigers. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN978-0812244526.

- ^Gunaratna, Rohan (1 January 1993). Indian intervention in Sri Lanka: the role of India's intelligence agencies. South Asian Network on Conflict Research. pp. 212–213. ISBN9789559519904.

- ^Seevaratnam, N.; Tamils, World Federation of (1 January 1989). The Tamil national question and the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord. Konark Publishers. p. 69.

- ^Aggarwala, Adish C. (1993). Rajiv Gandhi: An Assessment. Amish Publications. p. 5. ISBN9788190028905.

- ^Summary of World Broadcasts: Asia, Pacific. British Broadcasting Corporation. 1999. p. 6.

- ^'Wanted: VELUPILLAI, Prabakaran'. Interpol. 4 October 2006. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ^ ab'The Hindu: Time not ripe to give up Eelam goal: Prabakaran'. The Hindu. 11 April 2002. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^Assignment Colombo at page xv(15), ISBN81-220-0499-7, published by Konark Publishers Pvt Ltd, delhi

- ^S. L. Gunasekara (2002). The wages of sin. Sinhala Jathika Sangamaya. ISBN978-955-8552-01-8.

- ^Lawson, Alastair (18 May 2009). 'The enigma of Prabhakaran'. news.bbc.co.uk.

- ^Bermana, Eli; David D. Laitin (2008). 'Religion, terrorism and public goods: Testing the club model'. Journal of Public Economics. 92 (10–11): 1942–1967. CiteSeerX10.1.1.178.8147. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.03.007.

- ^Pape, Robert (2006). Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism. Random House. ISBN978-0-8129-7338-9.

- ^Laqueur, Walter (2004). No end to war: terrorism in the twenty-first century. Continuum. ISBN978-0-8264-1656-8.

- ^'UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights'. Hrweb.org. 7 July 1994. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ abc''Sun God's' Life of War'. Archived from the original on 12 November 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2009.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link). Straits Times, 18 May 2009

- ^Hoole, Rajan; Thiranagama, Rajani; (Jaffna), University Teachers for Human Rights; Lanka), University of Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna, Sri (2001). Sri Lanka: the arrogance of power : myths, decadence & murder. University Teachers for Human Rights (Jaffna). p. 227. ISBN9789559447047.

- ^'Prabhakaran is dead'. The Hindustan Times. 18 May 2009. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^'The last days of Thiruvenkadam Veluppillai Prabhakaran'. Lanka Web. 22 May 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^'Sri Lanka Army – Defenders of the Nation'. Army.lk. Archived from the original on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ^Bosleigh, Robert (9 May 2008). 'DNA tests on body of Prabhakaran, Sri Lankan rebel leader'. The Times. London. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^'Fonseka Refutes Karuna's Contention That Prabhakaran Shot Himself'. The New Indian Express. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^'Tamil Tigers confirm leader's death'. Al Jazeera English. 24 May 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^'Tamil Tigers admit leader is dead'. BBC News. 24 May 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^'Health card of Prabakaran is not so rosy as it ought to be'.

- ^'Archived copy'. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2017.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

- ^Dianne Silva (22 May 2009). 'Prabhakaran's body cremated'. Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009.

- ^'Last days of Thiruvenkadam Veluppillai Prabhakaran'. Daily Mirror. 23 May 2009. Archived from the original on 21 June 2009.

- ^The Independent, 26 February 2013

- ^Lawson, Alastair (28 May 2009). 'Tamil Tiger chief's parents found (BBC News)'. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^Sri Lanka Tiger leader Prabhakaran's mother dies

- ^Cousin wants Prabhakaran mother sent to Tamil Nadu

- ^Prabhakaran, Veluppillai and the father-son relationship

Further reading[edit]

- Rajan Hoole. (2001) The Arrogance of power, UTHR (J), Colombo.

- Pratap, Anita. Island of Blood: Frontline Reports From Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Other South Asian Flashpoints (2001).

- Chellamuthu Kuppusamy (2009). Prabhakaran – The Story of his struggle for Eelam. New Horizon Media Pvt Ltd. ISBN978-81-8493-168-6. Archived from the original on 17 November 2012.

- Chellamuthu Kuppusamy (2008). பிரபாகரன்: ஒரு வாழ்க்கை. New Horizon Media Pvt Ltd. ISBN978-81-8493-039-9.

External links[edit]

- United States Pacific CommandAssessment of Prabhakaran

- BBC Profile – The enigma of Prabhakaran

- BBC News Report – Reclusive Tamil rebel leader faces public (2002)

- Final Showdown for Tamil Tiger Chief PrabhakaranThe Times of India, 23 April 2009

- Claims of Massacre as Tamil Tiger Leaders Die by Robert Bosleigh, The Times, 19 May 2009

Prabhakaran Daughter Dead Body

Interviews and speeches[edit]

- 'Veluppillai Prabhakaran's interviews'. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2005.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- 'A short assorted list of his interviews'. Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2011.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

| Sri Lankan Civil War timeline |

|---|

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ |

Comments are closed.